Introduction by Timothy Leary

The 60s in America was different and difficult for all of us. It was a time of fast thinking, profound shifts of direction, and a lot of fun. The Doors of Perception were glued together by many souls. And we had in common a need for mutual dignity, freedom and passion.

This story is about a young man at 20 under the influence of art. He is in rebellion with his parents, Hollywood, America and the Arts. Growing up in Europe, meeting history on the walls of the Etruscan frescoes, walking the Tiber, and finding the fountains of Rome erotic and funny prompted his first calling to become an artist. His parents were artists in the film world. They were sympathetic to Michael’s odyssey. His picture of the eternal city was transposed from a Hollywood upbringing.

The book begins in Venice, California on an LSD trip with Jim Morrison, who is also looking for his identity. Their friendship helps define each of their paths. Michael’s world view, like Jim’s, tries to be hip. Where Michael’s optimism fails he finds his bravery and his imagination. The world feels in flux and his affection for people and their art forms become his faithful companions.

I identified with this naïveté. The riddle of life has several options, and Michael has the time to sort out his lot. He is lucky. We can study his boyish charm at leisure. I wonder if many young people today have the time to consider their privileges. Michael owes his parents a part of the freedom he explores.

This is a sweet story which suggests that the ultimate resolutions may not be the answer. This is no surprise. However, here is a wealth of impressions! People, places and events, famous and personal, sit side by side in curious metaphors that softly draw the reader into meditation.

This Lawrence trip catches something of this passion or faith and the landscape of the 1960s. It is, as a book, an interesting guide to a path we are now returning to. ‘Sight and setting’, or the organising of how to view reality, affects how we see the wonderment of creation itself.

The sight and setting focus around art provides subtle shifts that are illuminating, pleasurable and often funny. An adventure of rich feelings and a sense of human growth evolves.

Timothy Leary

July 1990

1

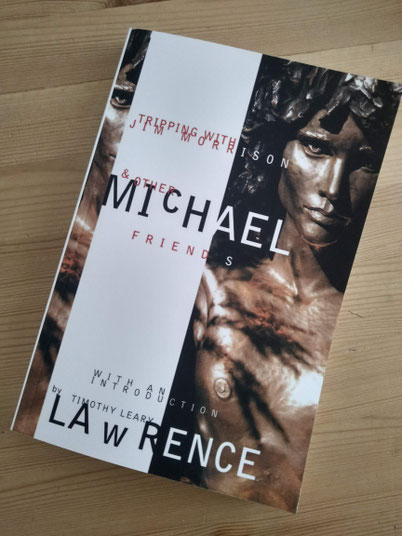

Tripping with Jim

I am sitting in Venice at the kitchen table going over some of my notebooks. It is my senior year at UCLA. Outside the light is fading and Morrison pops in. Felix has something special, do I want to join him and Phil? Before time for second thoughts Jim had charmed me into his fold. He had good timing that way; I was ready for a game. We were off on foot scurrying across the alleys like Huey, Louie and Dewey Duck the cartoon images of a Disney world, on our way to the Andes to find the precious jewels hidden deep in the Inca caves. We scurried across bridges past bungalow houses amidst a labyrinth of quaint structures. The glass chimes tinkled in the wind outside Felix’s bungalow. We were on the canal off Howland Avenue. Jim softly knocked on the front door. The afternoon light was as tentative as his rapping. There was no answer. Jim went around the back. I looked into the patterns moving across the water in the canal. Jim returned, he nodded; we left quietly and as quickly as we had come.

Those few moments we spent circling outside on the veranda of Felix’s bungalow gazing at the water created an unforgettable feeling as if I were in Kashmir far away from LA or this lifetime. It was a passing thought, a flash, and we were on the move again. Experience is a ball of string that each of us unravels. Fate, karma, destiny, character… it is all different for everyone. Would my own life be like my donating that painting to Jim’s door? Did I expect, require, demand that every gesture I make be acknowledged, put in a museum? Isn’t it all a museum? Aren’t we under the cosmic umbrella? Where else is there to go? Vanity. Who said it, ‘all is vanity’? Life and the living of it is the thing, even if beauty needs a place to rest. I was on the move following Jim, mindlessly enjoying, not thinking about anything, just out playing with the boys.

In the distance we spotted a police car. The black and white taxi. Jim suggested we outfox them. It was a grey winter’s day, no one else was out except for us; we looked automatically suspect. It was part of the game, to see if we could lose them, tease them a bit and then disappear into thin air. We crossed a footbridge to the other side of the canal, down an alley and up; we had gained time. We walked on more confidently now. They had missed us. We were now approaching the boardwalk that ran parallel to the ocean in front of a long bay of sand. The grey of the afternoon light had darkened. Along the boardwalk the palms shifted ominously in the cool breeze that was coming off the tops of the white caps foaming in the distance. Jim stopped in front of a small water fountain. I had forgotten that we had actually scored anything. Jim handed me a pill and bent down to drink some water. “I used to drink here, last summer,” he intoned in a manner suggesting fondness as he tilted his head to the side. Phil and I swallowed our trips. It was time to head for some shelter. Jim suggested that we drive over to his pad, which was on Fourth Street, as there was time before the trip would hit. Back at my place we jumped into my TR3 and drove the few blocks east.

We entered a small apartment with peace-eye throw rugs and wood panelling. As I was taking inventory of the pad, Jim immediately turned on the radio, which I noticed to be a large and modern set. He was crouched down to turn the knobs. He did this very attentively; he was completely focused on the radio. Jim had knelt down as if in front of an altar. A connection was being made in this moment of intense focus. To listen was to become one with the music. Later when Jim wrote about music being your only friend, I thought of this moment and what seemed like a communion. When he sang at the Unicorn coffee house he had pressed his boot to the stand of the microphone with this same sense of intense connection. The channel would be opened and the words came up from inside his body, travelled into the microphone to explode in the amplifiers as clear words on the sea of air, carving out of the waves the words of prayer, the song, the message, his soul. When Jim kneeled to listen to the radio it seemed an acknowledgement of all beauty. The nature of his own moves opened the channels and showed me the grace of his reverence.

Phil had already disappeared into another room. I felt slightly on edge, not knowing exactly what to do with myself. Standing in the door jamb, watching Jim deftly tuning the dial, I felt out of place, trapped. There was an empty room so I decided to lie down in it and take inventory: cool down, get a hold of where I was.

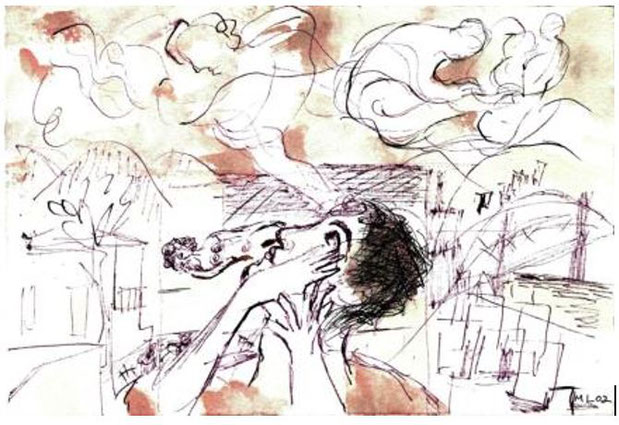

Lying on the floor the feeling of discomfiture seemed to be increasing and I felt nauseated. This was a typical reaction going into a trip, but it always affected me badly. I sat up in the hopes that I would feel better. Listening to the music I heard a blurred chorus of what I imagined to be giant frogs belching and burping outside. The room was claustrophobic. I got up on my feet.

I saw Jim leaving the radio and heading out the door. “Where are you going?” I thought I was saying, but he left without responding. I followed, but he had disappeared. I felt better outside in the dark air, comfortingly wet and frothy. There was a fog, a mist that hung around the lampposts, but I could see clearly. The plants, illuminated by the streetlights, appeared violet and fleshy. A car lurched in the distance. I found myself peeing. It felt warm. How long had I been walking? Do I live nearby? I was moving unconsciously through this dark world, aware only of moving and then I turned on all the lights in my apartment. How had I found the switches? I crawled into bed feeling my kidneys: large tubes of lipstick, full of blood, full of youth, a very rich feeling, overwhelming. Is someone talking to me? Who is there?

There is only the moment; so many thoughts and experiences coming and going in a small brightly lit theatre of images. Pick one and find the past parading in front of you, aping pleasure. They all seemed to have the same weight, as if meaning had no special importance, the moments of a life being mere sculptures. The mind empties, I am here in my living room typing, having spent the day writing, sculpting, going to the post and coffee between the rain in the fresh air. I am alive, rolling and unrolling a thread, sound the trumpet, I am grateful, ready for a new call to arms. The memory of having the sensation that William Shakespeare came to visit me that night and how flattered I was to have him near; looking over my shoulder as he passed, looking to find a new drama. Alas, I wasn’t writing anything on paper, it wasn’t necessary; it was all in my mind, especially how quickly he made off with all my ideas.

Voices seemed to be coming through the radiator. Jim had forgotten to turn off the radio. What are they saying? It’s in a foreign language, or is it Morse code? Damn, I should have studied that at school. What was it that Ginsberg was saying about the CIA? Is the radio taping me through the radiator? Where were my friends? What is a friend? Why did they have to kill me? I wouldn’t play along? Was it a kind of new Mafia or something? What was this LSD? A secret way of recruiting people, transplanting energies into other bodies, transforming your body? Where was Jim? I was sure he could answer all these questions. Where had he gone? How had he disappeared so quickly? Was I farting? I felt better. Was it getting lighter? How long had I been wrapped in bed? Could I find my way back to the apartment? I’d wait for dawn. It was odd to feel Shakespeare’s presence; maybe he thought this would make a fine play? Hamlet? I thought that the night had passed quickly. I had listened to the radiator as if it were monitoring me or I it. What a strange trip! I didn’t like thinking about the CIA or hearing voices over the radiator. It wasn’t amusing to live through, even if it was funny to think about later. It was a madness. And I’m not mad. A happy fool to be sure to expose myself to the wind, to see what’s flying. But when you are thinking thoughts that don’t feel like your own invention, then reality is another kettle of fish. That is an unholy monster of an experience, when you sense that you are not there, that it is not you who are thinking, a conscious nightmare.

Was it Jim’s reality? I felt there was something almost vicious about this acid, as if it had stolen into my consciousness and made off with something. With the sun came a sense of ease and just Willy Shakes and Rock’n’Roll. The morning air was fresh and I was genuinely pleased to see other people routinely going about setting up their shops for the day’s business. Passing a small park even the trees seemed pleased to see me. They appeared like sentinels, bright and peppy in the early morning sun. It was a sparkling blue morning, the first after a long stretch of grey ones. I had the impression that I was in another town. Perhaps Arles. The pine trees and the park had made me think of Vincent. A happy Vincent, the painter off to a vineyard in the morning sun before it became too brutal. I was too agitated to paint. There I was. This was the apartment. The door was open, so I entered. I called out but there was no answer. Turning around I was facing Jim, who just walked in as if that night had never existed and he was dropping in to see an old friend after a long period of absence. He threw his arm around my shoulder, delighted to see me.

“Got any grass?”

“Where have you been?” I responded, slapping the leaf of a plant as we headed toward the sidewalk.

“Don’t do that; don’t hit the plant.”

I acknowledged his request and asked him again where he had been all night.

“Oh, I was down at the beach, listening to the waves.”

“Wasn’t it cold?” I asked. Jim laughed.

He laughed himself into the back seat of my TR3 and wrapped his legs around my waist. Jim was so buoyant, full of cheer. It was clear to me he hadn’t spent the night listening to a radiator. The music had continued in his head, the waves playing softly. Had he composed some of his gentle lyrics about swimming to the moon and climbing through the tide?

The lyrics were clear and full, the gesture as open as his wrapping his legs around me.

I laughed and off we drove to my apartment. Jim and I bolted into the pad and sat down at the kitchen table.

“Where’s Phil?” I asked.

“He’ll show up,” Jim quipped; he was still laughing.

Examining the grass Jim suggested that we eat it rather than smoke it. Conveniently there was a jar of honey on the table, which we opened and dipped our hands into like cubs, then rolling our paws into the grass. The grass lost its bitter taste. We were pleased at our ingenuity.

There was a knock at the door. Phil came in and he and I looked at one another. We seemed to spring apart and fly through the air, as if some energy field existed between us rendering us non-compatible. This was phenomenal, yet meaningless. Like my paranoia. It was there however, and whatever that energy field had been, it did separate us, throwing us apart as if we’d been sucked into a black hole and shot out. In the future, we would never become close friends, but for that moment, in my kitchen, we all laughed it off and Phil joined in for our breakfast of grass and honey. The three of us sat in the small kitchen, the sky turning grey again. We gazed at each other, grunting. I had some trepidation about doing grass after my ordeal the previous night, but now I felt more secure amidst company. Nothing was said for the longest period as if we were catching our metaphysical breaths.

Then Jim broke the silence, “Shit!”

I sized this up and carefully responded mimicking his cool posture with a “Fuck.”

Jim in turn gave me a long hard look and then said, “Shit.” I volleyed back with “Sheet.”

He felt that this needed a decisive “Fuck.” I quite agreed, “Fuck.”

Between our exchanges of “Shit” and “Fuck” were thoughts silently placed that indicated exactly just how the ‘shit’ should sound and exactly what we meant by the work ‘fuck’. Indeed there seemed to be a real conversation going on between us. The weightiest bits of philosophy, our goals, our disappointments, the lovely ladies we had laid were all described in this manner, in the minutest details. The worldview itself, die Weltanschauung, everything lay between these two words. We had boiled it all down to a few syllables to record time. To give a simple sound the feel of a vast experience. There wasn’t much beauty to this, no real elegance, rather a symbiotic embrace of the void we would have to fill to become artists. For the moment, it was a substitute, a smug comment. Vietnam and middle class sheep sat at our sidelines, but we had no money, just sad shoes and attitude.

Throughout our exchange Phil sat nonplussed. Out of the silence he began laughing, laughing like a drunken gypsy. And then Jim and I understood what we had been doing and we began laughing as well.

This moment of brightness faded. “Do you want some tea? I mean to drink,” I asked. Phil thought he might have some. Jim’s head was drooping. “Are you okay Jim?” He didn’t answer; instead he fell into a stupor. I was concerned. I recalled that Jim had taken some tests at UCLA, that they had concluded he had petit mal or some such. I had thought that this was just a part of his cloak-and-dagger routine, but now I was alarmed. I reached for him and he, almost sensing my presence, raised his head.

He looked half asleep. He smiled that mischievous boyish smile, “Wanna go for a walk? I’m fine, man, hey, let’s go out, c’mon man, follow me.” Jim got up slowly, gracefully pulling up his body, summoning his strength. I turned off the water, which hadn’t boiled yet, anxious to accommodate Jim’s wish to be outside.

The mid-morning air was warm and it felt good to be out in the open without a roof binding our thoughts.

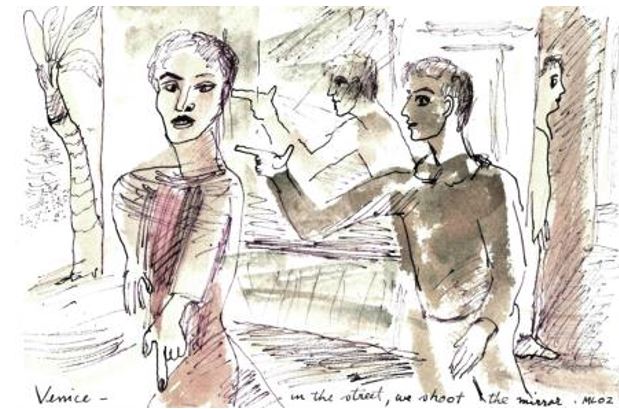

“Damn, my moccasins are still wet. I’ll just slip them off.” The pavement was warm.

Jim and Phil were a few paces ahead of me. I ran to catch up and decided to pass them by; I liked running. I stopped and turned, made my hand in the shape of a pistol and pretended to take aim at my companions, transforming the run into a game of Cowboys and Indians. Jim and Phil sprang into action; they drew their imaginary guns and ‘scuttled up’ to join me. The grey of the morning suggested an old TV serial western; Hopalong Cassidy, Roy Rogers and Gene Autry together for the first time. We were joining forces to right the wrongs of this here frontier town. Now we were cooking.

“Do you think they’re behind us?” I asked Phil, who looked at Jim who answered, “Yep.”

“Let’s go this way,” Jim indicated and pointed to the right. We were heading for the pass. They always headed for the pass.

I scouted the buildings looking for the bandits hidden between the boulders. I thought that I had spotted one; you couldn’t be too careful. My horse, my legs, were in good shape, we galloped toward the boardwalk. Around it goes, cinema, young boys pretend, reality on drugs, the reel, our real, projection of cinema onto reality. Guns, hunting, escape, hiding out forever and ever as boys will be boys, being men; endless cinema, endless wars.

At the clearing the grey sand melded into the grey ocean. At the boardwalk the sensation of a western faded and now we were in another film, a Godard flick, cinéma vérité. We stopped in front of a mirror to examine our appearances. I drew my gun and shot at the image reflected in the pitted surface. Dans la rue on tuais le miroir. I heard the waves crashing in the distance. Jim and Phil were twenty feet ahead of me. They were pinned up against a doorway. I came up behind them. Jim had a bit of the Jean Paul Belmondo about him: “if you don’t like the country, if you don’t like the sea, if you don’t like women, well man, go ‘F’ yourself.” All said, to be sure, sotto voce, never macho, standing as tall as you possibly can and shooting from the hip like Alan Ladd in Shane. Jim was studying a car in the parking lot across from us, beyond the green cupola. It was the only car in the lot. The lot was closer to the ocean than we were. Jim turned to me, quizzically and tilted his head, “Hey, man, go check it out.”

As I crossed over to the lot, cinéma vérité faded into the grey realities of a real street scene. I was standing twenty feet or so now in front of a sedan. I stopped, thinking it was odd for Jim to have sent me over. A slim black figure extruded itself from the passenger side. The voice of the young black man was very tender, very gentle, “do you want something, man?” The timbre of his voice came from another drug experience. “What do you want, man?” I shook my head indicating that everything was fine; somehow I did not want to break my silence. I turned around, headed back. I knew that they had been on heroin, I could feel it in his voice, and heroin was a drug that scared me. The sound of the young black man’s voice made a very gentle impression upon me. I’m damned sorry I didn’t open my mouth, I was scared but it wasn’t as if that meant I’d take the heroin. His gentle voice had a sense of promise to it. One, two, three, four, open the door, there is no undercover man. We all uncover some aspect of reality. Nobody can take what you don’t own. It’s where you put things, ideas, words, they already exist. That is what the radiator was trying to tell me. Don’t fall into a timid mode, keep it open. It’s all the same stuff piled up on a DNA strand in different amounts, orders, signals. I could have said, “hello, how’s it going?” Life is a participatory sport, so Harry, be kind to yourself and dive in. Thoughts are prayers, action is what is called for. Yeah, it wouldn’t have killed me to have said “hello”.

“What’s up?” Jim asked secretly knowing my sense of dislocation.

“Spades ruining themselves on junk,” I replied.

We walked back to my apartment; the spell of movie land had been broken. Jim decided to continue on with Phil. I climbed up the stairs and made myself a cup of tea.

Paperback

ON SALE

£5.00

$15.99

£9.99/$14.99

£3.99/$4.99