...my mother knew Jim as a college student, a young polite guy in khaki pants studying film at UCLA. She had made us pancakes one morning. She understood by his natural cool manner a form of intelligence. She liked him immediately; this pleased me, and gave her a chance to tell some of her stories. She could be the centre of attention as we had the house to ourselves. My father was away, busy with a film. We were used to entertaining ourselves when he was away. My mother was a writer. And so was Jim. I had my notebooks as well.

“Do you know the work of Paul Bowles?” My mother pulled from the air.

“Ah, he lives in Tangiers, writes about foreigners, how they are changed in Morocco removed from the familiar, other behaviour comes into play.”

“Perfecto!” Mom put her thumb to her forefinger, signalling that Jim had hit the bull’s eye. This was not surprising, as Jim had taken a course in set design in high school. He had conceived of using a spotlight, which would grow bigger as the play Cat on a Hot Tin Roof by Tennessee Williams unfolded. The growing light was to symbolize the growing cancer inside of Big Daddy, the patriarchal figure whom everyone wanted to please. Tennessee Williams was a popular celebrity in the early 60s. Paul Bowles had done the music for his plays and it was known that he wrote. The ‘beats’: Kerouac, Ginsberg and Burroughs, had visited Paul in Tangiers. This scene is also familiar to young people interested in avant garde literature.

“We threw a party for Tennessee in Rome, in the early fifties. Has Michael told you of our stay in Italy?”

“I didn’t go into Paul Bowles, Mom.” I had liked Jim’s idea for the play, but I hadn’t told him about my mother or that she wrote plays.

“Paul brought the hashish.” My mother liked to shock. Jim uncrossed his legs and looked into the hazel eyes and pixie face that had addressed him. “The Sirocco wind was blowing that night. We had a large terrace and the gathering included many old friends: Richard Basehart and his beautiful Italian bride, Valentina Cortese, who was a star then, and Paul had a few friends, and of course Tennessee Williams. The warmth of the Sirocco can put you into a trance, get under the skin, make you crazy. It is an unpredictable force.”

Jim’s head had tilted and it was clear that my mother had an audience. She liked to paint moments and took her time selecting the colours.

“All at once Ten’s laughter would cackle through the air. We were smoking hashish in cigarettes, which had an effect like the wind, unpredictable. Large eucalyptus trees across the street swayed, their leaves made a rustling sound. They looked like strange gigantic creatures, rattling our subconscious with vague suspicions. Under the influence of our smoking, the occasional passing car added a kind of B-movie element of suspense. Basehart, who had been sitting next to Valentina holding her hand, got up for a drink to quiet his nerves. He had recently finished a film for Fellini which hadn’t as yet been released. My husband was jumpy. He wanted to play the lead in the film Richard was discussing, Fellini’s next project, La Strada. Basehart was fond of Marc. My husband’s desires can be overwhelming. It is his intensity. He knew he would be perfect for the part that eventually Tony Quinn played.”

Jim nodded. My mother’s voice had slipped into a southern accent giving her description a theatrical touch.

“Tennessee was playing a game with Richard, suggesting that sex appeal was a fragile commodity; like perfume it could evaporate or drive people away. He can be a little devil, that Tennessee. He was clever never to suggest that Dick had a problem, but with the hashish and Paul’s Moroccan friend who was wearing a burnoose, a surreptitious atmosphere was created. Tennessee was reading fortunes, looking at the cards. Then abruptly his laughter would break loose. It’s a high-pitched hyena’s cry, electrifying. ‘For Christ’s sake Tenny, write me a play and stop torturing, Dick,’ my husband said in a menacing tone.

“Tennessee released another volley of laughter, pleased with himself.” My mother was smiling, recalling the night. “I wrote a play in the next two days. I couldn’t sleep, it poured out.”

Was Jim fascinated? We were familiar with the dreamy realities of grass. I had heard the story. She had told it well for Jim.

“Michael smokes in his room, I can smell it. He listens to that terrible Indian music,” she shot me a glance of ‘oh well’ and faced Jim. “Do you enjoy smoking that rubbish?” Her statement was in odd contradiction to the benefits she had just spoken of but there was no tone of malice to her voice, rather a sort of bemused acceptance of youth’s experimental period.

Jim was gazing out the window. He turned, smiled and then addressed my mother speaking slowly. “It’s research. Sometimes I write a lot under the influence, I can be happy to watch what is happening around me… it changes the point of view. You look at yourself looking. That is what is neat. You look at yourself looking and so what you observe is something which you are also creating. It’s kind of… what I think Wittgenstein said about observing reality, that it responds to your looking like a whistle a guy gives to a pretty girl; reality is winking back at you or winking because you are looking at it.” Jim was smiling and then he added, “I’d like to read your play.” I was glad he had sidestepped what is a boring subject of conversation.

“Well, it’s another kind of game now. I don’t know… read it!”

“I like the forces you play with Mrs Lawrence. I’ll write down my observations for you to read.” Jim wasn’t trying to be presumptuous, he merely wanted to put his scholarly side to some use and mom was pleased by his offer.

“I think that would be fine, but it isn’t necessary to address me as Mrs Lawrence. We aren’t that formal around here.”

My mother began to talk about her own youth. She had taken her own father to court because he had thrown her boyfriend out of the house. Edward Dahlberg, a writer, was several years older and he wrote about the sexual habits of animals and insects and their strange affection. My mother had secretly married him. She was a bohemian herself.

“Well, Mrs Lawrence, I’m real pleased I’ve discovered a new friend.”

My mother laughed at Jim’s over-playing at being polite.

“You know Jim, I can remember being three years old… I found a jar of cherries soaked in liquor. When my father Noah came back, he found me sitting on the kitchen floor, schicker… you know, drunk. We both started to laugh.”

There was a pleasant pause in the conversation.

“Ah, I guess we should be going,” Jim said.

“I wrote a novel about this period.”

“Was your novel ever published?” Jim asked at the door.

“It was optioned for the movies, but sadly the war came and it was never made. Ask No Return. I have it somewhere, but read my play, it’s much more contemporary.”

“I’ll look after it.” Jim held it close. “Thank you again for the pancakes and the lovely conversation.” Jim politely extended his hand. We walked to the garage and to my car. I could tell Mom had really enjoyed talking to Jim. He was a good listener. I think it was also neat for Jim, a hip mom, with whom he could be himself. Of course how is one to know all of this if I don’t tell you? But then who is to say if the differences of our upbringing didn’t also give us something in common and focused us to go our different ways? But I won’t talk about that part first. The important thing is that we fell into life’s tavern and knew we had mutual friends even if they existed mostly in books.

c. Michael Lawrence 2016

All rights reserved

Extract from

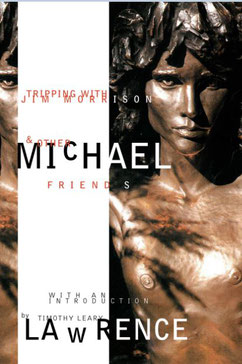

TRIPPING WITH JIM MORRISON & OTHER FRIENDS

An artist's search for beauty, art and identity

by Michael Lawrence

5 SEPTEMBER 2016

Paperback £9.99/$14.99

Ebook £3.76/$4.99

ISBN 9780993307034 Paperback

ISBN 9780995473508 Epub

B&W 6 x 9 in or 229 x 152 mm

250pp