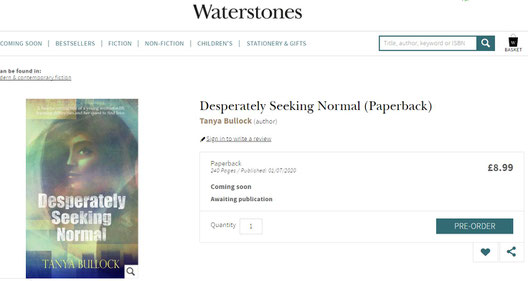

Desperately Seeking Normal

by Tanya Bullock

Chapter 1

mother and daughter

Izzie: I have very little memory of the night Jaya was conceived. In the weeks and months that followed, the vague recollections I did have were so surreal and sexy that, had it not been for the gradual expansion of my waistline, I might have attributed them to some bizarre erotic dream. Now, almost twenty years on, even those hazy memories have faded; like ancient coffee-coloured photographs with gently curling edges, the specific detail is blurry and soft.

Strangely however, a few snapshots from that evening have become imprinted on my mind in startlingly sharp focus. I remember a picture-perfect sunset, two empty bottles of Cobra Beer in the sand, the smell of fried fish, the dopey, plodding cow which blundered a path through our love-making (I wish I could forget the cow), the Arabian Sea before me, the gritty taste of sand in my mouth – and him: an outline moving in the shadows, a supple and angular body, a hungry mouth on my neck, an intoxicating scent of coriander and cologne. My daughter’s father is nothing more to me than a collection of random memories and yet, on the rare occasions when I permit myself the luxury of steamy thoughts, I always think of him.

Jaya: I live with my mum in Netherton. Netherton is a good place to live because it’s next to Merry Hill, which is my favourite place in the whole world. Merry Hill is probably the biggest shopping centre in England and I go there nearly every Saturday with my mum. Mum is white, but I’m only half white. My other half is Asian. I’ve never met my dad, but Mum says he’s from India. I’ve never been to India, but I’ve got lots of pretty saris, which is what Indian ladies wear. I don’t have any other family, apart from my grandparents, but I’ve never met them because they’re racist.

Izzie: I’ve always had a high tolerance of parental disapproval. At some point in my early childhood, I reached two important conclusions:

a) that it was unrealistic I would ever become my mother and father’s ideal daughter and,

b) that it didn’t actually bother me.

Life was much simpler after that. When, at sixteen, I informed them that I would no longer be accompanying them to church every Sunday, I endured the ensuing torrent of criticism and condemnation with calmness and composure. When I came home with a nose-ring at the age of seventeen, my parents didn’t speak to me for over a month and I enjoyed the peace and quiet.

Similarly, when at eighteen, I dropped out of college and hopped on a plane to India, I did so with full peace of mind. Upon my return a year later, I faced my parents’ wrath with my usual sang-froid before serenely dropping another bombshell: I was four months pregnant. Incensed, they invoked God the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit to rain down upon my head a plague of locusts, pestilence and venereal disease (or words to that effect). I was a whore, a Jezebel, an ingrate, a wayward slut of a daughter, a source of intense mortification and shame. I accepted all insults with grace and good humour, picked up my backpack and left.

My inherent immunity to the opinions of my parents remained intact until Jaya was born. From then on, all that mattered to me was what was best for her, which presented me with somewhat of a predicament: how did a selfish, conceited teenager with no partner or real friends, no money, no qualifications and no home, go about providing a stable upbringing for her infant daughter? For the first time in my life, I needed my parents and felt sure I could rely on their strong sense of duty.

Devout Christians, they would undoubtedly forgive their prodigal daughter, slaughter the fatted calf and welcome their grandchild into the family fold. Admittedly, the signs were not good. I went through a lonely, complicated and painful childbirth at Russells Hall Hospital.

Afterwards, the space around my bed on the maternity ward was conspicuously empty of well-wishers. I lay there during the first few befuddling, bleary-eyed days of motherhood, aware of other new mothers and their families sneaking sympathetic glances in my direction. When I was released from hospital, I returned to the women’s hostel where I had spent the last four months of my pregnancy and, apart from an endless stream of concerned health professionals, I had no other visitors. For six months, I did nothing but care for my baby and re-evaluate my life. I eventually managed to convince Social Services (and myself) that I was a fit mother and emerged from my self-imposed solitary confinement a responsible adult. I was ready to face my parents.

One bitter morning in January 2002 found me, babe in arms, standing on the front porch of my parents’ austere white semi. Trembling with cold and nervous anticipation, I took my courage in both hands and rang the bell. The door opened and the familiar form of my mother appeared before me. I searched her eyes for a glimmer of maternal feeling and was rewarded with the weakest of smiles. My heart soared as I held Jaya up for her to see. My mother peered at her grandchild over her glasses.

‘She’s very dark-skinned.’

‘Her father is Indian,’ I replied, my hopes of reconciliation squeezed as flat as the thin line of my mother’s lips.

‘Indian?’ she said, as she might have said ‘Martian?’

‘Oh, for Christ’s sake!’ I snapped.

The whiteness around my mother’s tightly closed mouth spread to the rest of her face.

‘Do not take the Lord’s name in vain.’

Her hypocrisy stunned me into silence.

‘If you’re going to come in, do it quickly,’ she hissed. ‘I don’t want the neighbours knowing your shameful little secret.’

I looked at her and, in that moment, understood why for all those years I had so systematically rejected her values and shunned her approval.

‘Good-bye, Mother,’ I said as I turned to walk away. She didn’t try to stop me. That was the last I ever saw of her.

Jaya: I go to college three days a week to do Life Skills, English, Maths and ICT. I like Life Skills and English, but I don’t like Maths or ICT. Maths is hard because you have to learn about money, which means you have to add up the things you want to buy, then hand over the right coins and then count your change.

I like buying things, but I’m not always sure what each coin means. Mum lets me buy one thing every time we go to Merry Hill. Usually I buy nail-varnish or lipstick. My favourite colour lipstick is Autumn Apple because browny-red is the hue which best complements my skin-tone. I found that out on the internet. I know a lot about make-up. My mum never wears it because she says she’s beautiful enough. I tell her she should wear foundation because she’s quite old and has wrinkles. She says I’m a cheeky wench. She makes me laugh. My mum is my favourite person in the whole world.

Izzie: My tiny daughter entered the world on a sweeping wave of change which engulfed me, overwhelmed me and spilt over into every area of my existence. The woman who holds her child for the first time is never the same woman who conceived that child. Her body, lifestyle, clothes, dreams and future plans will all have been altered to some lesser or greater degree. Personally, my initial response to motherhood was a full-blown identity crisis. I felt that, as I had given life to Jaya, she had taken mine. I lay in my hospital bed, the same three words whirling round my head: Who am I?

Before Jaya, I could have answered this question in a flash: I was a loner, a firecracker, an adventure-seeker, a sex-bomb, a go-getter. Men wanted me. Women envied me. No more. I held my newborn in my arms, my sense of self in tatters. It was a bad case of the ‘baby blues’. Luckily, my hormones soon settled down and my maternal instincts kicked in. I was flooded with love for my baby. It was a love like no other: it soothed my troubled mind, healed my aching body and filled the hole where ‘me’ once was.

Jaya: My best friend at college is Kerry Holt. We’re the prettiest girls on the Life Skills course, everyone says so. Kerry’s boyfriend is called Ian Kennedy. I haven’t got a boyfriend, which isn’t fair because I’m actually a bit prettier than Kerry Holt. Kerry and Ian hold hands at lunchtime and sometimes they kiss when they think no-one’s looking. I kissed a boy once at a Mencap disco. I had to sit on his lap because he was quite short, but I didn’t mind because he was a really good kisser.

Izzie: I always knew that there was something wrong with Jaya. I knew it long before her paediatrician confirmed it. I knew it when she was eight weeks old and didn’t respond to my voice (‘All babies develop at their own pace,’ the health visitor reassured me). I knew it when she was a toddler and constantly bit her hands in frustration (‘It’s the terrible twos,’ my GP explained patiently). But I knew differently. I knew Jaya. When she turned three and still couldn’t say ‘Mummy’, my GP finally took me seriously and referred her to a paediatrician.

I took an instant dislike to Dr Moore. He was a bearded, condescending old dinosaur, who had so patently never been a child himself that I doubted he would have the first clue how to help my little girl. For her sake however, I banished my concerns, put on a brave face and took Jaya to see him on several occasions. Over the next year, Dr Moore ruled out various disorders and conditions with complex and frightening sounding names. Jaya didn’t seem to have ADHD, dyspraxia, conduct disorder, Heller’s syndrome or epilepsy.

As each possible illness was crossed off his list, I became increasingly anxious. How could I support Jaya if I didn’t know what was wrong? I also had a more selfish reason for seeking medical opinion: I desperately needed reassurance that the cause of Jaya’s developmental delay wasn’t bad parenting. In the continued absence of a formal diagnosis, the ‘fault’ lay squarely with me.

Then, on the day before her fourth birthday, Dr Moore informed me that he was discharging Jaya from his care.

‘Have you found out what the problem is?’ I asked him.

He nodded. ‘Her inability to respond appropriately, lack of expressive language, deficiency in memory skills and difficulty in processing new information all point to one obvious conclusion –’

I was on the edge of my seat. ‘Yes?’

‘She has significantly impaired cognitive abilities.’

My heart hit the floor. It had taken twelve months for the pompous old fart to tell me what I already knew.

‘Can’t you be more precise?’

‘Not really,’ he replied. ‘Jaya doesn’t have a diagnosable condition. These things happen. I can’t do any more for her, I’m afraid.’

These things happen. His words rang in my ears. These things happen? That wasn’t the answer I wanted. I shook my head in disbelief. There were still so many questions I needed answering. These things happen. How? Why? How do you cope when they do?

a new teaching assistant

Izzie: Jaya’s remarkably sprightly this morning. She seems really excited about going to college and spent much longer than usual on her hair and make-up. She even went to the effort of putting on her ‘party eyes’: a thick line of liquid mascara on each eyelid, topped with a smudge of glittery eye shadow.

‘Anything special happening at college today?’ I ask her over breakfast.

‘No,’ she replies, stuffing a spoonful of cornflakes into her mouth.

‘Then why the party eyes and the chignon?’

I can tell she’s not listening to me. Her eyes are on the kitchen clock and she’s practically hovering over her chair.

‘It’s quarter-past-eight,’ she says, proudly.

‘Well done,’ I say. It’s actually quarter-to, but I don’t want to dampen her newfound enthusiasm for telling the time. ‘Now sit down properly and eat your breakfast.’

She reluctantly pulls her chair closer to the table.

‘Now,’ I continue, ‘what’s the big rush and why are you all dolled up?’

At that moment the doorbell rings.

‘Ring & Ride,’ she exclaims as she jumps up from her chair. ‘Bye Mum. Love you.’

She blows me a kiss and is gone. As soon as I hear the door slam, I reach for the phone and punch in Bee’s number. Kishan answers with his customary heavy breathing and suppressed giggles. In the background, I can hear Bee telling him he’s going to be late for the day centre.

‘Day centre, day centre, DAY CENTRE,’ he bellows. I hold the handset at arm’s length; Kishan has a very loud voice. After a short struggle, I hear him relinquish the phone to his mother.

‘You’re through to Bina’s Madhouse. Admissions department. How can I help you?’

No matter how bleak I’m feeling, Bee can always make me smile.

However, this morning I’m in no mood for light-hearted chitchat. I quickly tell her about Jaya leaving for college dressed like Miley Cyrus.

‘Do you think there’s a boy involved?’ she asks.

‘There could be,’ I reply. ‘Do you think I should be worried?’

Bee goes quiet and I know she’s considering how best to advise me.

‘If I were you,’ she says eventually, ‘I wouldn’t be overly concerned. So what if she does have a boyfriend? She is eighteen.’

I suppress a groan and close my eyes. In my head, I see a montage of romantic moving images: Jaya and boyfriend holding hands at the pictures, Jaya and boyfriend sucking on either end of the same strand of spaghetti, Jaya and boyfriend sitting on a park bench – he whispers something in her ear, she giggles, he leans in to kiss her … my eyes snap open.

‘I just don’t think she’s ready, that’s all,’ I say.

‘Of course you don’t,’ laughs Bee, ‘you’re her mum.’

Bee’s insouciance does nothing to lighten my mood and I remain sullenly silent.

On the other end of the line, Bee sighs and changes tack. ‘Cheer up, sweetie,’ she says, ‘you know what Jaya’s like about her appearance. She’s probably just trying out a new technique she’s seen on some beauty vlog.’

I hang up and feel relief wash over me. Of course, Bee’s right. Jaya’s probably just experimenting with a different look. Nothing new there. I laugh at my own paranoia. If I got my knickers in a twist every time Jaya donned a new sari or curled an eyelash, I’d be a nervous wreck.

Jaya: There’s a new teaching assistant at college. His name is John and he’s so sexy. I can’t wait to get to college today to see him again. While I’m sitting on the bus, he’s all I can think about. I can hear Kerry and Jo talking about him, but I don’t join in. It’s much nicer to just sit here and daydream about him.

The bus pulls onto the college car park and I quickly pull out my little mirror. I check my face and apply a bit more lipstick. I hope John likes my party eyes. I think I’m in love!

Izzie: After filling my head with nonsense, I now feel an urgent need to clear it. I pull on my overcoat and head out into the murky morning. I close the front door and am reminded of how much I used to hate that it led straight from the living room onto the street.

I don’t mind so much now. Now that I know where to find all the local hidden gems, the unruly youths and swirling crisp packets barely even register. In half an hour, I can be tramping the towpaths of Dudley Number 2 Canal, or bimbling through Bumble Hole, or admiring the cliffs of Doulton’s Claypit. I set a brisk pace, a luxury I can only afford when I walk alone, as I’ve never met anyone who can keep up with me. I walk up Hill Street, passing St. Andrew’s Church, which is one of my favourite haunts. For some reason, browsing the inscriptions on eroding gravestones has a calming effect on my soul. But not today. Today my soul needs water and so I head over the crest of Netherton Hill and begin my descent towards Lodge Farm Reservoir.

Jaya: John isn’t in the car park to meet me this morning which is actually quite annoying because I’ve spent ages on my hair and make-up. Maggie’s here instead and she smiles and says good morning. I say good morning back, but it isn’t really a good morning because Maggie’s here to meet me instead of John.

Maggie walks us all into college and I buy a cup of tea from the cafeteria because it’s still early and I’ve got ages yet until my first lesson. So, I’m drinking my tea and minding my own business when suddenly there are two hands over my eyes and I know for sure they’re John’s from the lemon soap smell. Guess who? says John and I say Kerry as a joke which makes him laugh a lot. Then he sits down and he’s so close to me that our shoulders are touching. He smiles and asks me if I’m OK and I’m so excited that I actually forget to breathe and I feel like I need a wee but I don’t.

Izzie: I sit and take stock on a roadside bench, staring at the choppy waters of the former clay pit. Beyond the reservoir, Saltwells Wood is just about visible through the morning mist. I love this area. It is steeped in industrial history, once teeming with the workers from collieries, pits, quarries and mills, now reborn as quiet woodland and green open spaces. I breathe in the filmy air, thick with the secrets of this rich and ancient land.

A car zooms past me and I catch a glimpse of an errant baseball-cap, facing backwards on its owner’s head. A boy-racer, no doubt on his way to meet his yobbo mates for an illicit morning car-chase. I follow the foggy trail of exhaust fumes towards Merry Hill, with its enticing network of roads. It seems impossible to me that a shopping centre and a nature reserve can co-exist in such close proximity. But then that’s the wonderful thing about living here: no matter how urban and built-up it may seem, there’s always a rural escape close by.

Jaya: This is the best day ever! I was eating my lunch with Kerry and Ian when John came over and sat by me again. He’s sitting next to me now and smiles at me whenever he sees me looking at him. Usually when a boy keeps looking at me and smiling, he ends up asking me out. I wonder if John wants to ask me out? I whisper this to Kerry and she laughs and says no way stupid. But Kerry’s always been jealous of me so what she says doesn’t count.

Izzie: I hug my coat to my body in an attempt to preserve the delicious melancholy of Saltwells Wood in the brooding fog. Bee passes me a sandwich and a mug of tea.

‘The heating is on, you know,’ she says, her black eyes twinkling.

‘What do you mean?’ I ask.

She motions towards my thick duffle coat. ‘I know this old stable is a bit draughty, but it isn’t that cold.’

I giggle at this wildly inaccurate description of her home. Everything in her snug terrace kitchen oozes effortless style, from the vintage mannequin bust by the window, to the bold Mirό prints on the wall.

‘What’s up with you anyway?’ she demands.

‘Just a bit nostalgic.’

She rolls her eyes. ‘Been skulking around the nature reserve again?’

Bee has the uncanny ability to read me like a book. It used to bother me, but not anymore.

‘All morning,’ I chuckle. I put down my plate and give her a big bear hug. ‘Do you remember the day we first met?’

‘Oh, my life!’ she exclaims. ‘You were such a cow, I’m hardly likely to forget.’

I laugh out loud at this. She’s right. I was a cow. It was in the playground of Jaya’s primary school on her very first day. I was watching my little girl trot across the tarmac, surrounded by children with various disabilities: kids with Down’s Syndrome, kids in mini-wheelchairs, kids hobbling on crutches, kids with guide canes, kids with hearing aids. I waved Jaya a cheery goodbye, struck suddenly by the seeming unfairness of it all. All those tiny individuals were so diverse and unique, that it just didn’t seem right to lump them together under the banner of ‘disability’.

That got me thinking. Where exactly did Jaya fit in? She didn’t have a physical disability and her problems seemed relatively minor when compared to those of some of the little mites braving their way across the school playground. The more I studied Jaya’s young classmates, the guiltier I felt over my decision to send her to a special school. In that moment, I was ambushed by my old enemy, Panic, who fired questions into my brain, like painful, explosive little gunshots. Is this the right environment for her? Would her specific needs be met? Would she fit in? (If so, would she be sufficiently stimulated and challenged?) Would she feel lonely and alienated? (If so, would the experience leave her traumatised and withdrawn?)

I was just on the point of chasing dementedly across the playground and dragging Jaya back home, when I felt a friendly tap on my shoulder. I turned to see a vivacious-looking young woman grinning chummily at me. She nodded towards the crowd of children.

‘Which one’s yours?’ she asked.

I pointed at Jaya.

‘The Asian girl?’

‘Mixed race,’ I corrected.

‘Of course. So, your husband is Indian?’

I shook my head, but offered no further explanation.

‘Pakistani?’ she persevered.

‘No,’ I replied abruptly, hoping she’d get the message and bugger off. However, the woman seemed undaunted by my frostiness and continued to smile affably at me.

‘Perhaps you’re not married? Are you divorced? Widowed? Or maybe she’s adopted?’

Her persistence astounded and infuriated me. The nosey cow could not take a hint.

‘She’s the product of a drunken one-night-stand, OK? Her father could have been black, brown or blue for all I knew or cared!’

I stared defiantly into her eyes, awaiting the inevitable shock and disgust, but instead, my future best friend threw back her head and laughed. Her mirth was genuine, warm and infectious and it melted my icy armour. I extended my hand, shyly.

‘I’m Isabel.’

‘Bina,’ she said, still giggling, ‘but you can call me Bee.’

I turn to Bee now. ‘Fourteen years ago,’ I sigh. ‘Blimey, that’s gone fast.’

She puts her arm around me. ‘You OK?’ she asks. ‘I was a bit worried this morning when you started going off on one.’

I shrug. What can I say? I never feel fully in control when it comes to Jaya.

‘She’ll be fine,’ says Bee, reading my mind yet again.

‘I hope so.’

I give my best and only friend a kiss on the cheek and head for home.

Jaya: I wave good-bye to John from the steps of the Ring & Ride. Bye John I say and he says good-bye sweetheart. Sweetheart! That’s what boyfriends say to their girlfriends. Now I know for sure John wants to be my boyfriend. I want to be his girlfriend too.

Copyright 2020 Tanya Bullock

All rights strictly reserved

Not to be reproduced in whole or in part without permission from the publisher

'Manages to combine a sensitive subject with Black Country Humour.' 'WATERSTONES LOVES', WATERSTONES, WALSALL

'A wonderful poignant and witty story.' JILL FRASIER, Founder and Director of healthcare charity, KISSING IT BETTER

'If you enjoy Mike Leigh films you will love this book.' GOODREADS

'Akin to The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time this novel will hopefully inform people, in much the same way, about young people living with disability, and their individual rights and feelings.' GOODREADS

'This is not like any other novel I have ever read. It tackles major taboos head-on, but the author does it in a way which is so sensitive and witty, you wonder why they were ever taboos at all!' GOODREADS

'I was knocked out by the quality of the writing and predict a glowing future for the author. She really does know what it takes to write an unputdownable and unforgettable book.' US AMAZON READER

Waterstones

US Amazon

UK Amazon