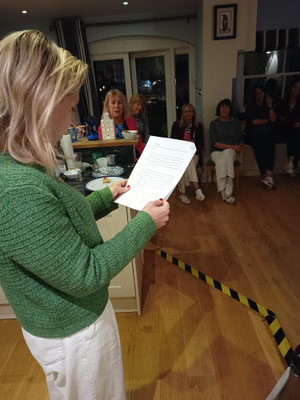

The winners of CWWL's annual Summer Writing Competition have been announced.

The competition is an annual event, open only to students of Creative Writing Workshops London, run by Blackbird author Diane Chandler and Blackbird editor Stephanie Zia.

Many thanks to Diane for another fantastic party and to Maddie Chandler for stellar admin duties ensuring all entries remained anonymous until the winners had been picked.

Much love and thanks to this year's guest judge the author, arts producer and adventure activist Jessica Hepburn. Jessica is the only woman to have completed the Sea Street Summit Challenge (swimming the English Channel, running the London Marathon and climbing Mount Everest!). Check out her website to read about this amazing person's life adventures and books.

We had a tough task shortlisting so many great entries, we were, however, unanimous in our decision on the 5 winners. Many congratulations to:

1st Lucie Wignarajah On the Ropes

2nd Jeremy Brown Faith

3rd Paul Simpkin Birthday Wishes

4th) Yema Redfern Zero Hour

4th) Ricky Cibardo Murder with a Splash of Milk

Read the winning entries below.

First Prize: On the Ropes by Lucie Wignarajah

“We have two lives, and the second begins when we realize we only have one.”― Confucius

I don’t know when I first noticed it, but the voice in my head would start narrating my action until it became a daily habit. “He walks to the window and opens the heavy taffeta drapes. a stream of sunlight pours into his hotel room. It’s going to be another scorcher today here in Nevada”. I guess this must be partly down to my career as a broadcaster, the occupational hazard of a commentator or is it just my mental illness?

I can’t help narrating action in my head. “He sits on the edge of his king-sized circular bed and picks his tux off the floor; he pulls out ten ‘thousand-dollar bundles’ from the pockets”. Sometimes I even pretend I have an audience, makes an average day a bit more thrilling, gives it a shine. “Ladies and Gentlemen” I say to myself “He’s made it. Dominic Levine has made it" Yes, sometimes I even refer to myself in the third person, people say that’s a sign of narcissism, don’t they? “He’s in the Emerald City. The MGM Grand, Las Vegas, and he feels like the god damn Wizard of Oz!”

“He swings his legs out of the bed and into his black and gold MGM monographed slippers. This, my friends, is the year of boxing, both in the ring and on the silver screen” I continue to observe my action like the omniscient narrator “He walks into the bathroom and looks into the mirror” I admire my image and shadow box Rocky style in front of it. I select James Brown from the CD rack. All the while I’m chronicling my every move. “He dances over to the hotel safe holding his cash to his chest. OH look, he’s hopping from foot to foot, he’s dancing like a loon”. I’m wearing a silk boxing style dressing gown wrapped around my skinny frame. “Oh dear, He’s pouring himself a large whisky now and it’s only 10am” I pour a drink into a crystal tumbler from a decanter and look out at the orange morning of the desert.

It’s 1999, I’m here at the MGM Grand to commentate on a historic clash between two titans of the ring, Lennox Lewis and Evander Holyfield.

I narrate the action as if I’m watching myself. “His make up is touched up, the lights are hot and he’s sweating. Lewis, A heavyweight boxer, ten years his junior, Levine, a journalist sitting at ring side in a pale blue suit, whose only ever hit a pillow”.

Everything feels aligned. My voice is revered. I feel like I’m singing to the arena. Two fighters stand toe-to-toe in the centre, exchanging blows in a furious dance of fists.

Thousands of expectant fans watching, and ME at ringside. I hold my breath and I've never felt a rush like it, and then there’s silence. My mind is clear, and I feel peace. It’s a spiritual peace, as quiet as a Roman cathedral, vast and cold and flagged with cool marble, a priest swings incense through the aisle of my mind, and I feel whole, holy. “Holyfield..right–left, ohhh…Lewis… he’s been up with 33 punches..he’s down.. down. Holyfield is back. this doesn’t look good for Lewis” …

After the fight, we hit the casinos with their towering facades. I’m in my mecca. The whole strip meticulously crafted to dazzle and deceive. The air is thick with desperation and hope. Mere shells tethering gamblers to their seats. A vast illusion.

Me and my entourage speed to the opulent halls of Caesar’s palace. The first thing that strikes me is the sheer grandeur of the place. A Roman Empire theme, from the towering statues of Caesar to the intricate marble columns and gold leaf trimmings. This is a setting fit for high rollers like me. I’m almost spinning on the casino floor, all 124,000 square feet of it, this glorious gambler’s paradise.

But for me it’s the titillating thrill of those tables. Ahhh the blackjack, craps and roulette! My God, the stakes are high, but the potential for big wins is even higher. Cirque de Soleil spiralling in the background, the Mirage’s volcano erupting with splendour, the marvel of the Bellagio fountain which pipes to the tune of Sinatra. What time is it? Fuck knows. 3am. Don’t stop me now. I’m on top of the world, but then at the bottom of the ocean. I am on quicksand, the floor moving under my feet. I can almost feel the plates of earth shifting beneath me.

Why do I return to the tables again and again? The roulette spins, almost in slow motion, and there’s silence, I can breathe again.

It's a surrogate Mother, it's a father’s hand on my shoulder.

My father, coldly packing me off to my school. Him, distracted with his business. Me, waiting for him to turn around and wave goodbye.

And then I don’t have a choice, I have to take away these feelings, they are too big for me. I’m so scared at the memory of being left at that large school entrance hallway, so frightened of seeing my father walk away, that all I could do was walk up to that croupier again and stop the feelings, hush the fear. What if Dad finds out? I've borrowed money from him, turned it into liquid to pour down the sink. It runs and swirls away from me in front of my eyes. It’s lost its value, £100,00 could be £100. The digits are all just wild calculations in my mind, Monopoly money. I'm spinning away from my life. Gripping on to the belief that the next big win will help me break even and then I'll stop.

I’m a boy, ten years old and away from home. I’m unpacking my case. Putting away folded uniform into dormitory drawers. Arranging my teddy bear at the foot of my bed.

Back in London, I watch myself on the evening news, a grimace etched on my face, parroting the auto cue while my hands and body are shaking with anxiety.

I stagger home, my mind racing with calculations. Two mobile phones and a pager in my pocket. One for bets, one for loan sharks and one for my family.

“What the fucking hell have you been playing at Dominic? What the fuck have you done” My wife screams at me down the family phone. “What else have you been hiding? TELL ME! You owe it to us, to me, to the kids.. we’ll never get over this Dom, we’ll never forgive you”.

I can't think, my mind is holding 50 thoughts. I'm finding it hard to have a conversation or even construct a sentence with my head full of numbers. £144, £645, £155,000. £5786 … Gambling addiction is an elusive force, a scaled animal sleeping in the corner who suddenly opens one eye and looks at me. It's bigger than me. It's bigger than us. I can't control when it wakes, it's hungry and needs feeding.

In bookies on the high street, I watch myself objectively “He walks in and fills in the betting slip with a mini biro, the size of his little finger”. You'd think they'd offer ink and quills in the bookies and wax seals or gold-plated pens. I was signing away all my savings with a toy biro.

By Millenium eve, I have nothing left. Bankrupt, bailiffs chasing me, I’ve been fired, and it is my last day at the BBC. About to be the year 2000.

The streets riddled with new year revellers. Portland Place is black and shiny with January rain, slick as an otter’s back.

The sky growls: a band is tuning up at the 229 club. people are drinking Guinness in an Irish pub, a woman is singing to a baby, an organ plays in Old Souls Church in Langham place, a man is holding out a McDonald’s cup in a doorway, the tube rumbles deep beneath the city.

The lights of Oxford Street twinkle with festive decorations in every window. Christmas trees wobble and bow with the weight of hanging baubles. I think about my wife, how disappointed she was that we couldn’t do Christmas, there was no way I could buy presents for the family. I’m a useless father, a piece of shit husband, a disappointment of a son.

At the bottom of Portland place. the BBC building is alive with activity, Runners scurry the corridors, anchors read from autocues, the news desk-a hive and big screens flash up with New Year’s countdowns from around the world.

Eric Gill’s statue of Prospero, a symbol of power, control and redemption, looks on with cool ambivalence at the scene.

The sky is ink black. A bright moon disappears behind navy blue velvet clouds, lighting them from behind. A stage lit for the final act; a moon beam falls on our actor.

It calms me down to be the director, it removes me one step from the terror of what I’m about to do.

“Here he is on top of this iconic art deco building, British Broadcasting House. He has spent a lifetime here, behind a mask, but tonight it is off”

Antony Gormley has made sculptures of men and placed them on rooftops around London, menacingly purveying the city, surveillance in dark rusted bronze. I’m smaller than these dominant oversized statues. I’m tall and slim; my demeanour is clerical. I’m told, and I have a slight stoop. But I’m dressed immaculately, even today, the day I plan to kill myself.

Behind me, the breathing memorial, an inverted conical statue commissioned to commemorate journalists killed in action, beams light into night sky, making me look like a ghost.

I had dressed that morning, as usual, from my collection of tailored suits which had been paid for by the BBC. Just this morning, I “watched myself” pick out a special suit for the day.

“He brushes his hands across a line of suits and picks his favourite, placing it across his forearm and admiring it as though he’s about to dance the waltz with it”.

I had planned this final act meticulously like every other part of my life, which had been controlled and ordered. This was just another diary event to be scheduled. The time, place and event neatly recorded.

I continue to commentate from the roof “Oh he’s close to the edge now, a sheen of sweat on his brow and his top button undone, his tie discarded somewhere near the reporting desk”.

“Good evening, ladies and gentlemen! Welcome to tonight’s exciting fight which promises to be a classic in every sense of the word. In the red corner we have a seasoned veteran, known for his tactical prowess and resilience. This has been a tough day for this old dog” I say out loud, catching the view far below. I look down again, steadying myself on a safety fence. “Hmmm the crowd is buzzing with anticipation, but this guy. He’s staying heavy on his feet, using endless angles to keep the crowd guessing”. Down below at the end of Regent’s Street, a crowd has gathered, some in Y2K costumes. A grim reaper looks up, sensing the black irony of his costume.

“But this fighter is not backing down Ladies and Gents, you can see the experience in the veteran’s movements” I peer over the edge at a sea of London traffic, orange and red glowing lights swim beneath me. My job is to act in front of a camera, unclenching my jaw for the audience. And then off camera, back to clenching.

I stand still on the roof, ten thoughts fighting for attention in the ring of my mind. My wife, my mum, my dad, my kids, the debt collectors, my co-presenters, my boss, my addiction, my boarding school, my beautiful boxing heroes.

Ambulance and police have been called and the blue lights, urgent and dramatic arrive at the scene.

My mind flashes back to last year in the MGM Grand, Lewis-Holyfield. I had the fever, the heady intoxicating rush of the flutter. The surging. The feeling was implanted then and could not be shaken.

I remember my dormitory at boarding school. A pair of binoculars, a chess set, stringed boxing gloves hanging on the bed post, my teddy.

And in the next few minutes, I am the hero of this story.

A fighter. A diver. An Olympian. Finally, nothing matters, nothing exists. There are no debts, there is no time, no days, no hours, no memories. Just this moment. Quiet. Flying, floating, descending.

My “family” phone rings in my pocket, I can’t reach it.

It’s Dad.

It rings and rings and rings out.

c. Lucie Wignarajah 2024

All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission

Second Prize: Faith by Jeremy Brown

The taxi was already pulling away. The woman standing on his doorstep was small. Her two suitcases were on the pavement beside her. He stood in the open doorway, unsure, unwilling to invite her in.

‘Hello, Mr Sharp. I’m Faith.’ She extended her hand. He registered her bright red coat, her hair crammed under a woollen hat, a few tight curls escaping, a friendly smile, before she said.

‘May I come in?’

It was too late to take her proffered hand. She had already reached down to her suitcases.

‘Yes.’ His tone was grudging. He stood back, trying to get his walking stick out of her way without losing his balance. Welcoming someone to stay who wasn’t a friend, or relative, still rankled although it was not the first time. He knew she came armed with knowledge about him, his disabilities, his frailties, his medications and much else. There was probably a fat file in one of her cases. He hated it, hated her, hated the necessity.

She stepped into his hallway, facing him. What was he supposed to do?

‘At least be polite.’ His daughter had warned him. ‘Don’t just be a grouch.’

Against all his instincts, he waved his hand at the house beyond the hallway, intending a general welcome. Faith smiled again and then said.

‘May I take my cases to my room?’

‘Oh, yes, top of the stairs, first left, bathroom’s on the right.’

She moved past the stair-lift, taking one suitcase, reappearing quickly for the second. He watched, impotent and wary, as if a burglar was being given carte blanche to check his possessions. Worse, it was a legitimate intrusion.

His daughter had been too eager, he felt, to slough him off, removing her belongings from her childhood bedroom to accommodate this stranger, consigning the dirty work to someone else.

‘It’ll make your life so much easier, dad,’ she’d said, as he’d watched her take her things out to her car. He couldn’t find the words to argue back. It was an empty room, yes. She hadn’t slept in it for years, true. Yet her few, remaining possessions had been a slender thread connecting him to happier times. He’d stood in her doorway, sometimes, just looking. He’d wanted her to leave something behind, anything, but it had seemed pathetic to ask. Then Irina had arrived, Polish, cheery, alien, the first of them, the first of the uninvited.

‘I’ll be down in a few minutes and we can talk about your requirements,

Mr Sharp.’ Faith’s voice brought him back. He nodded, turning away to his sitting room, his stick catching the carpet’s edge. He sat in his armchair, feeling anxious, as if some form of interrogation lay ahead. He glanced around the room, seeing it as she would see it in a few moments, the tired furniture, the photographs of his daughter and his dead wife, the ornaments he no longer noticed. He knew she was his lifeline, but what to, exactly?

Faith came into the room.

‘May I sit here?’ She pointed to the other armchair.

‘Yes, yes.’

‘I know you’ve been given my details.’ She continued, sitting down opposite him, her skirt and blouse different shades of green, both straining to fit. She paused. ‘But just to be sure, I’m Faith Sibanda. I’m from Zimbabwe. Well, my parents were. I’ve lived here a long time. May I call you Andrew, Mr Sharp?’

Wanting to say Mr Sharp would be best, but accepting with a nod, he looked at her carefully, as if the details might tell him something important. He noticed her stockings ended just below her knees, the tight elastic tops creating slight bulges of flesh above. Her shoes were scuffed, brown leather. He doubted she was paid well. He looked away. He wanted her to be as minimally human as possible. A stranger in his home might be more bearable if they were less real. She went on.

‘Thank you. Irina and I spoke during her last week with you.’

This was said with a bright smile, as if to reassure him. It had the opposite effect. What would Irina have said? What presumptions had Faith come with? He resisted saying he hoped Irina had spoken well of him. He didn’t care, really. His resentment was far stronger than any wish to be friendly. He nevertheless felt he should say something, if only not to seem too incapable.

‘Irina was a bit sloppy.’ He wasn’t sure that was exactly true. She’d spilt his

tea a couple of times and once went out for her day off without doing the washing up. ‘Well, sometimes.’ He added, lamely.

‘I’m very meticulous about tidiness and hygiene.’ Faith wasn’t smiling now. ‘Don’t worry about that.’

‘Oh.’ He found himself reluctant to engage in a conversation about her attributes. Couldn’t she simply do her job and leave him in peace? Yet he knew that was a doomed hope. Her job entailed looking after him in intimate ways. He’d been appalled when Irina helped him in the shower and the lavatory. She’d done so with cheerful casualness, but he’d felt humiliated, doubly so because he knew it was necessary. Her rubber gloved hands had seemed to suggest he was already decomposing, his flesh slack between her yellow fingers, his skin grey against the bright colour.

‘We will have to get to know each other.’ Faith was smiling again. ‘Then I can help you more.’

His spirits sank. He wondered if he could set boundaries to this invasion.

‘What do you have to know?’

‘Well, Andrew, of course I already know lots of basic things, your prescriptions and dietary needs, but I don’t know you as a person. Irina didn’t tell me much, just that you like to spend time in your garden, you read a lot, you have a daughter who comes to see you most months, and so on.’

He wondered if it was true that Irina hadn’t said much. She’d made him angry on several occasions. At one point he had told her to get out. She’d gone up to her room, crying, but when his evening meal was due, she’d reappeared, pretending nothing had happened. He’d felt remorseful. He knew he was unreasonable. Sometimes everything seemed so hideous, his weakening body, his memory loss, the world passing his door as if he’d already been excised. He’d wanted to tell her his anger wasn’t personal. He hadn’t said it, though, and it was personal, really. Everything was.

‘I’m not sure there’s anything else to tell you.’ He hoped this would end the conversation.

‘I’m always interested to learn about what my clients did, their work, their lives before they retired. Some things don’t get onto our files.’

He was about to respond that his past wasn’t any of her business, but Faith didn’t stop.

‘You can tell me when you’re ready. There’s no hurry. I’m not going anywhere.’ She laughed. It seemed oddly threatening.

‘Can I look around the kitchen so I know where things are?’

Refusal seemed out of the question, however tempting. He made as if to stand. She raised a hand.

‘Don’t get up. I’ll just have a quick peek. If I have any questions, I’ll come back. Would you like some tea?’

He nodded, watching her as she left the room. He strained to hear what she was doing, but apart from the kitchen door closing, he couldn’t tell. She returned, a cup of tea in one hand, a plate of biscuits in the other.

‘I hope it’s how you like your tea.’

The milky colour filled him with gloom. Should he say something, or was it too soon to seem displeased?

‘Thank you. Did you find everything?’

‘Oh, yes. There are things I’d like to rearrange, if it’s ok with you.’

He wondered what she might be planning. Some part of him wanted to check and perhaps object, but he didn’t have the energy. Shrugging, he told her it was fine, sipping his tea. He wanted to turn the television on and withdraw into himself. He’d told Irina he liked his own company. She’d said she understood, but it hadn’t stopped her coming into the room without warning. He’d considered asking her to stay in her bedroom, or the kitchen, but he hadn’t found a way of putting it that didn’t sound offensive.

Who was in charge of whom? He thought it probably wasn’t him, in the end, who made the rules. How had that come about? Faith said.

‘I’ll go and unpack. Then we can talk. It’ll be time for your supper soon, won’t it?’

She stood and walked past him, leaving the room without closing the door. He considered closing it, but feared it might seem pointed. He started retrieving the television remote which had slipped down in the chair beside him. Preoccupied, he didn’t notice she’d returned. He finally found the device, pointing it at the television, pressing the on button. Only then did he realise she was standing, watching. The slight shock caused him to squeeze the volume control. For a moment, the sound was deafening, disconcerting. He stabbed at the button, trying reduce the noise. Faith reached over, gently taking it from his hand.

‘Shall I?’

He stared up at her, wanting to shout that she had no business interfering. Now the television was quiet, he could hear himself breathing. His hands were shaking.

‘I came back to ask if you need anything, before I start unpacking?’

‘It’s my home.’ He was trying not to cry. ‘My home. I don’t know you.’ He was going to add that he hadn’t asked her to come, but he wondered if, in fact, he had. He looked down at his knees where his hands rested, the veins dark against his pale skin. They didn’t seem to be his. With an effort, he raised his head to look at her.

‘I’m sorry.’ He sniffed. ‘Will I have to die for you to leave?’

Faith stared down.

‘Andrew, Mr Sharp, what on earth do you mean?’

‘I don’t know.’

c. Jeremy Brown 2024

All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission

Third Prize: Birthday Wishes by Paul Simpkin

“Happy 7th birthday, darling.” Mum and dad sang happy birthday. I joined in. There was a big cake in the middle of the table with 7 candles on it. I had to blow out the candles, which I managed at the second attempt. Then they handed over my present. It didn’t look like a football. It looked like a book. I ripped off the paper and it was a book. “The Wind in the Willows” by Kenneth Grahame. At the time I was a bit annoyed but I grew to love the book. I had been enjoying the TV series so my parents thought that I would enjoy reading the actual book. I loved the characters. I loved the sense of companionship and friendship. It was one of the books that inspired my love of reading. It was a treasured possession and they had inscribed it with the words “Happy seventh birthday with love from mummy and daddy”. I’m not sure where it is. I think I must have given it to the charity shop with all my other books that I don’t have room for now. I wish I had kept it. It would be something to help me remember mum and dad. I kept it for a long time. I don’t think I would have kept a football for so long even if they had given me a football. The football would probably have burst on a rose bush or been run over by a car. But Wind in the Willows opened a window to something that was even more exciting than football – a world in which a group of friends were having adventures.

“Happy 14th birthday, darling.” Mum and dad sang happy birthday. I didn’t join in. As usual, there was a big cake in the middle of the table with candles on it. I can’t remember much about the party except it wasn’t much good. It wasn’t the sort of cake that I wanted. It was a bit childish. They hadn’t got me the right presents. I’d given mum a list of things that I wanted but for some reason they had only got a few of them. I was still annoyed that they hadn’t let me go on the school trip to Austria. All my friends were going. They said that they couldn’t afford it but I thought that wasn’t the real reason.

“Happy 21st.” Mum and dad sang happy birthday. There were balloons and a cake. My parents had bought me a watch. I put it on and thanked them but secretly I was a bit disappointed. I had heard of friends at university who had been given a car for a 21st present or a skiing holiday so a watch didn’t seem like much even though it was a nice watch. We had sandwiches to eat. A typical family birthday party. Not very exciting but at least it was better than my 18th which had been a total disaster. For my 21st I was home from university for the Easter holidays. Being 21 was overshadowed by the fact that I was starting to think about which jobs to apply for. Should I try for the civil service? Or be more ambitious and try for something less risky? The party for my birthday should have been a time to celebrate but it felt like I was at a crossroads, a crossroads that would determine the rest of my life.

“Happy 50th.” The assembled group of friends sang happy birthday. We were in the pub in the room that I had hired. It had been difficult to decide who to invite. I had spent almost 30 years working in the civil service. It was hard to believe that I was now 50. I didn’t feel 50. The prospect of retiring in 10 years filled me with a mixture of apprehension and anticipation. I felt that I had so much still to achieve. My attempts at getting promotion had been mixed. I was still trying to climb the ladder at work but I knew that I was competing with people in their 20s and 30s and that experience counted for very little compared to energy and enthusiasm.

“Happy 60th.” An old friend had sent me a What’s App message wishing me a happy birthday. There was no cake. There was no birthday party. I was treating myself to lunch in Wetherspoon’s. Nobody at work knew that it was my birthday. I had moved into a different team so that I could work just two days a week and prepare myself for retirement. I had thought about getting together with some old friends but decided that I couldn’t be bothered with all the fuss. I kept checking my phone to see if anybody else had remembered. There was a text from somebody that I used to work with. I looked on Facebook to see how many people had wished me a happy birthday. I had 97 friends on Facebook but only 10 of them had actually gone to the trouble of wishing me a happy birthday. I amused myself by making a list of all the things that I am going to do when I retire: go on a cruise, go camping in France, get an allotment, go on holiday to Austria, go on the Norfolk Broads with a group of friends, watch Michael Portillo’s latest series of railway journeys on iPlayer…

“Happy 70th.” The carer had brought me a small cake with a few candles on it. Of course to have 70 would have been too much. It might have burnt down the nursing home. She started to sing happy birthday but none of the other residents joined in. I could have smiled politely and wheeled my wheelchair back to my own little room for a bit of privacy and to watch the birds through the window but I decided to stay in the lounge as I knew Pointless was starting in ten minutes. I would be able to enjoy my favourite programme while munching a nice big slice of cake even though it was bad for my diabetes. So I took a really big mouthful and almost threw up. “You can eat as much as you like,” said the carer, “I made it without any sugar as I know you are diabetic.” I smiled weakly and tried to swallow the cake as best I could. Then she gave me a present. It was a book. I just about managed to get through the paper. It was a copy of the “Wind in the Willows”. “Hope you like it,” she smiled. “I found it in a charity shop and thought it might be your sort of thing.” The book looked very familiar. I opened it up and found written inside the front cover the words “Happy seventh birthday with love from mummy and daddy”. I had to pretend that I wasn’t crying.

Extract from funeral oration delivered by his nephew at the funeral:

As we all gather together to celebrate the life of my dear uncle I am sure that we all have very different memories of him and of how much he meant to us. I will always remember him enjoying cake at family birthday parties although sadly that probably contributed to the diabetes that caused many of his health problems and led to his sad passing earlier this month at the age of 70. One of his many other pleasures was watching the TV quiz Pointless and I know he spent many happy hours in the nursing home enjoying his favourite TV show. He once told me that if he had been able to take part in the programme then almost certainly he would have taken home a prize of at least £1,000 as he had devoted his life to finding pointless answers to pointless questions. (pause for laughter) I know that a couple of his ex-colleagues from his days in the civil service from his many years in the Department of Administrative Affairs are here today and they remind us of his many years of service in the civil service and the fact that he was a popular and well-respected colleague. They have shared with me an anecdote from the time when he was – and I must get this exactly right - Assistant to the Deputy Director of the Administrative Affairs Administrative Unit for the Administrative Affairs Brexit Change Project. He and his colleagues were involved in no-deal planning for Brexit and were brainstorming possible solutions to how a Hard Brexit would affect the maintenance contracts for the photocopiers in the department. Uncle offered his suggestion “If we don’t have any functioning photocopiers we could go back to what we used to do when I first joined the civil service and copy every document using a bottle of ink and a quill.” (pause for laughter) In retirement uncle was able to fulfil his ambition of having an allotment and it was lovely to see him pottering about there trying to grow vegetables and more importantly getting to know his fellow allotment owners, a couple of whom are here today. So finally, after his passing I was sorting through Uncle’s possessions and I found a book, which I think must have been one of his favourites. It is “The Wind in the Willows” by Kenneth Grahame. And just as uncle has now completed the final chapter of his life I would like to finish by reading a short passage from the final chapter of that book: “Sometimes, in the course of long summer evenings, the friends would take a stroll together in the Wild Wood, now successfully tamed so far as they were concerned; and it was pleasing to see how respectfully they were greeted by the inhabitants, and how the mother-weasels would bring their young ones to the mouths of their holes, and say, pointing, “Look, baby! There goes the great Mr.Toad!””

I know my uncle always took a great delight in the natural world and always valued friendship, as his many friends who are here today can testify. Wherever he is now, I hope very much he can feel the wind in the willows.

c. Paul Simpkin 2024

All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission

Joint Fourth Prize: Zero Hour by Yema Redfern

Chapter 1

The Night of Broken Glass

09 November 1938

Glass was not made to be broken. Neither were bones. But that night the shattering of windows only preludes the cries of grown men as they are thrown down the stairs, beaten on the streets, and dragged off to unknown destinations. Fast asleep in their home, Lena tosses and turns as if somehow she knows the fate that is about to befall them. Her father peeks through the blinds for the seventh time that hour. There is movement outside and he jumps to his feet so quickly that he knocks over the chair he had been sitting on and it crashes to the ground. He swears and, at the sound of his voice, Lena opens her eyes.

“Stay here,” he says. He pulls the blinds shut and walks out of the room, tiptoeing across the corridor and down the stairs. Lena sits upright in her bed, listening to his footsteps. A loud bang echoes through the night, a persistent knocking so abrasive it feels as if the front door is about to fall down. Lena slides out of her bed, slips her bare feet into her slippers, and quickly follows her father down the stairs and into the shop beneath them.

He stands in the dark, his hands on the back of his head, and she clings to the door frame as she spots the silhouettes outside. Three, maybe four men, uniformed shadows, surge towards the shop door, like ants to a sugar cube. They carry weapons: pickaxes, sledgehammers, knives, and they launch themselves into the door, the wood splintering and cracking with every blow.

“Father,” cries Lena, running forward so that she is beside him, and he balks at the sight of her, still in her pyjamas, moments away from the fires that burn and the city that has come alive for all the wrong reasons.

He spins around and picks her up with ease, as if she were much younger than her eleven years, bundling her into his arms, but before he can start for the staircase there is an almighty thud on the window to the right of them. The glass shakes, the sound reverberating all around them, and the two of them watch, mesmerised, as the hammer strikes – once, twice, three times – the silhouette of a giant outside, lunging forward with each stroke.

Her father retreats as the hammer continues to pound into the middle of the glass. After one more thwack, the window gives in its fight and the glass comes crashing down, like a rain cloud releasing all of its rain at once. Shards glimmering with colour cover the shop floor, skating across the floorboards. While the men outside lunge for the watches that had taken pride of place in the window, Lena’s father takes the distraction he needs to dive back to the staircase, pulling open the door to the cupboard that sits underneath.

“Quick, in here,” he says to his daughter and she folds herself into the space, nestled between a shoe rack and a pile of tablecloths. He glances quickly at the men filling their pockets and then his hand flies to his wrist. In one practiced movement, he unclasps his watch and hands it to her. His pale blue eyes find hers one more time and he gives her a terse nod, before closing the cupboard doors so that Lena is suddenly enveloped in darkness.

Heavy metal boots crunch on the shattered glass as the men make their way into the shop, the acrid scent of alcohol emanating from them.

“Jew,” a high-pitched, rasping voice screeches and that word, that one word, causes goosebumps to rise up Lena’s arms so sharply she feels that they are bubbling away inside of her too.

“Joseph,” her father replies, his voice so firm and unafraid it makes her swell with pride and regret her own fear, which wraps around her like a snake.

“Jew,” the voice re-iterates and, as his harsh metal footsteps sound on the floor, Lena takes the opportunity to shuffle sideways, craning her neck until her right eye is level with the keyhole.

The blonde man who had addressed her father stands directly opposite him now, with his back to her. He is thin and tall, like a beanstalk, but his lack of muscle is irrelevant when he carries with him a crowbar. He swings it around with such assurance it seems almost an extension of his hand.

“You will open these cases,” he says. The other two uniformed men draw closer.

“Please, no,” says her father, his voice carrying less confidence now, “It is my livelihood. My life’s work.”

“You will open these cases,” the man spits, “Now.”

Joseph glances to his left at the workshop, where Lena knows he keeps the keys, but it is as if that movement alone has broken the Nazi’s threadbare patience and with a roar he swings his crowbar at the cabinet, carrying it through the glass and out the other side. Tiny fragments fly through the air, shimmering and dancing. The men sweep upon the cases like vultures, smashing their weapons into the cabinets and scooping up the silver watches as if they are nothing more than penny sweets. Lena squeezes her father’s watch as tightly as she can, wondering whether she might be able to squeeze it hard enough that she could stop time itself. She squeezes so hard it hurts her fingers, but nothing changes. The Nazis work their way through the entire shop, taking every watch they can lay their hands on, while the watchmaker mourns.

When they have nothing left to take, they turn their attention to Joseph, closing in on him. The cold metal in her palm is the only solace Lena has as the blonde man’s knee connects with her father’s stomach and he falls to the floor, gasping for breath. The second man, whose pockets bulge from his loot, kicks his foot out and Lena gasps as it connects with her father’s jaw and his head smacks backwards onto the ground. Before the man can kick out again, one of his cronies, the blonde man with the crossbar, sticks out his arm and stops him.

“Wait,” he says, crouching down beside Joseph and pulling him up by his wrist, “What kind of watchmaker does not wear a watch of his own?”

Joseph’s head lolls so that Lena can see him now in full view. Blood runs down his chin and onto his crisp white shirt and his eyes glaze over, as if he were beside Lena in the tiny cupboard rather than on his knees.

“Someone took it,” he mutters, “Earlier today.”

The man laughs, a cold, callous laugh that makes Lena shudder, “A watchmaker, who cannot tell the time. How ironic.”

He lashes out at Joseph again who slumps over, and then he turns to the others and says, “Come on. Time to go. Bring the Jew.”

They nod obediently and two of them lean over, grab her father by either arm and drag him towards the shop door. As she watches her father, a man turned to mannequin, Lena longs to jump out from her hiding place, to run to him, to protect the only person in this world who has ever protected her. But her feet remain wedged in to the back of the cupboard and her hands will not move. They just cling to the watch her father has left her, willing the minute hands to wind back until she is alone with him again.

*

When Lena is sure the men have gone, twenty, perhaps thirty minutes later, she nudges open the cupboard door and clambers out. The cool air from outside rushes in now that they have no windows. She takes a few delicate steps forward, eyes on the ground in order to avoid stepping on any of the shards of glass that litter the room. She has to be brave, she thinks, like her father.

She tries to open the door that leads back upstairs but it locks when it closes and she does not have a key. She returns instead to the cupboard to retrieve a pair of shoes and places her father’s watch on her own wrist, securing it as tightly as the clasps will allow. She clings to the comfort of wearing a timepiece that has not only been worn by him, but was fashioned by his hands. He is still with her – even though she has no idea where he actually is. Where they have taken him. But she cannot dwell on this; it makes her heart cry out to imagine what has become of her father. She has heard the stories, the rumours. Sometimes they are so bad, she covers her ears in class to drown out her fellow pupils, and now she is living it. Her father is her constant, her anchor; he has to be ok.

Now she has proper shoes on, she walks over the glass more assuredly, checking the cabinets as she passes by, just in case even one watch face might remain. A watch strap even. But there is nothing.

With one last look around the defeated store, Lena makes her way to the shop door, which is hanging off its hinges, and steps outside. She has the same sensation one might have soon after it has snowed – it is as if she is entering a new world, one that is familiar and yet unexplored. Streetlamps on a foggy night make the dust in the air leap and glitter around her. A carton is carried by the wind, somersaulting down the road. Lena looks in the direction it has come from, biting her thumbnail as she inspects the scene before her. The pavement is half-concealed by a flood of milk, the smell of which reaches her nostrils around the same time as the sweet, not yet rotting, scent of fruit, barrels of which have been knocked over and cover the greengrocer’s entrance. Bunches of grapes reduced to liquid, squished underfoot, bruised apples, bleeding plums. The Nazis have not smashed his windows, but rather taken a bucket of paint to them, where someone has written in large red letters, Juden Raus. Jews Out.

Lena walks the other way instead. The neighbouring shops, the non-Jewish shops, are conspicuous in their silence, they lean back into the darkness, untouched, unspoilt. As she reaches the end of the road, what she sees when she turns the corner makes what little courage she has left drain away and Lena suddenly feels so small, in a world that does not want her. The hazy sky glows orange. A deep, dark orange contained only by a huge black plume of smoke rising up from the domed roof of the synagogue. She places two fingers on the watch around her wrist and presses down on it, until she can feel it making an indent on her skin. She shivers, and then turns back. She does not want to return to the shop, but she does not know what else to do. She has never felt so alone.

Lena keeps to the shadows on her way back, stopping and glancing around every few seconds, in case anyone should be following her. Just as she is approaching the shop, she hears the sound of a latch opening and a window above her creaks open. She pretends to ignore it, to keep walking, but a whisper in the dark stops her in her footsteps. It is her name. Someone is calling her name. She spins around and looks upward, bracing herself to run, but it is a familiar face that looks out at her. Frau Lehmann – the same elderly woman that had snuck her a bar of marzipan when she had fallen over in the street one day, who still visited her father’s shop, even when the Nazis had introduced a boycott against Jewish businesses. She smiles tersely, her hair pinned above her head, the sleeve of her nightgown waving in the wind as she gestures to Lena.

“Quick girl,” she says, “Come in.”

Lena hesitates, looking up and down the road, back at her neighbour, and then into the distance where the fires rage.

“Quick,” Frau Lehmann repeats and the urgency in her tone forces Lena forward and through the front door, which she now sees has been left ajar.

She closes it quickly, turns around, and almost yells out in shock as Herr Lehmann stands in the dark corridor waiting for her, his kind brown eyes creasing as he beckons her through to the living room.

“It’s ok, Lena,” he says, in a soothing whisper, “You’re safe now.”

c. Yema Redfern 2024

All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission

Joint Fourth Prize: Murder with a Splash of Milk by Ricky Cibardo

I stared intently at the drunk driver who murdered my wife as he sipped on his morning Latte.

His habits were like clockwork. Every morning, he departed his house to drop his kids off at school, turning left at the petrol garage before making his way through the beautifully picturesque Aber Village. He would grab a tabloid from Mr Archer's newsstand and go to the comfy chair in the second back row in Mrs Beecham's quaint coffee shop. At this point, I would join him and sit directly behind him every morning without fail. I knew how wrong it was and did not truly understand why I was doing it. Today is the same as it's been for the last three months. Here I am again. I was watching him. Maybe I wanted him to break down in front of me, visibly and audibly, even a mild heart attack to watch him suffer, possibly just an apology. An apology for everything he had done to me and my kids. That would be a start.

I have seen his name repeatedly in the court documents, and even though his name is known to me, I can't bring myself to use it anymore and give him credit for humanising the disgustingly fat weasel.

It was March 10th when I watched my wife Carla die in my arms, only long enough to tell me something inaudibly that I have convinced myself must have been that she loved me.

I glanced up at the drunk driver as he was failing his breathalyser four times over the legal limit. The arsehole that killed my wife cried and tried to put his arm on my shoulder as a means of comfort; Lucky I didn't break his arm there and then, but I was sat wrestling the Paramedic as he tried delicately to take my Carla from me.

He knows I am here. He gives a quick glance as soon as I order my Skinny Latte. I always emphasise the word skinny loudly with a hint of sarcasm in reference to his larger frame. Childish, I know, but I just want to get to him; I want a reaction. I never get one.

Until a few weeks ago, I was a prolific sender of messages to his Facebook account. Some messages called him every disgusting name I could think of, others just telling him how great a person Carla was, some crying into my keyboard at how he could have made 2 children motherless until I was ordered to cease all communications with him.

I blame myself.

Of course, he already knew how great Carla was. There was no need to tell him. I guess it is part of the recovery process. Pass the whole blame to him and give myself a fighting chance to start life over again.

His Latte bounced from his large paper takeaway cup, forcing a sudden movement, spilling a drop onto his poorly ironed white, collarless shirt. In embarrassment, he looked around to assess who was watching. His eyes caught mine. His were full of remorse, mine emotionless.

Well, my eyes looked emotionless, more the fact that I froze as it was the first time we had made direct eye contact since that fateful day.

I am a shit father.

I have stopped my little Dylan from meeting up with this drunk's son Joshua since it happened. 5-year-olds don't understand, but the thought of any association with a Holloway fills me with complete dread. There, I said it. Holloway. I wished his surname matched the establishment he should reside in. He got away with Community Service. The clean record and the unusual mitigating circumstances meant that I had to come to an agreement with the courts.

I was unsure how to take his half smile and half grimace that he gave me. On reflection, it probably wasn't remorse but more an attempt to gauge my reaction. He struggled uncomfortably with the plastic, white lid that had now fallen off his coffee cup before turning his newspaper over to read the sports pages.

Carla loved sports; she supported Liverpool FC, but I never held that against her. We named our first-born Ian after Ian Rush, but it was a common name enough for him to be able to change that narrative as he got older.

It dawns on me every day that he could choose a different place to drink his morning coffee. Maybe he secretly wanted to broach a conversation with me. Perhaps he knew I would follow him wherever he went, a kind of Mexican stand-off until we give up. I won't.

I smiled inside at the bruising on his left cheek. My friend took offence to what he had done, so gave him a few quick hits. Luckily for him and my friend, the police were already responding to a petty theft and were close by to prevent any further damage. I hope he was damaged in more places on his body that aren't as visible. I will pretend that's the case. Yes, a few sore ribs and a cut to the abdomen will do for the fantasy for now. The fact is my emotional scars will never heal; they will always outweigh his physical pain.

He will have emotional pain. I feel the same emotional pain, but I won't acknowledge that.

I wanted to die last week. I had enough.

I can't leave Dylan and Ian orphans. That is all I kept saying to myself, and the kind person whose name escapes me at Samaritans concurred.

Truth be known, I felt worthless for the entire year leading up to Carla's death ever since I found out what she had done, what they did.

I should have acted sooner. If I had, I might still have a wife or at the very least, Carla would be alive. She was only 45 years old when she died; she was relocating to Canada and wanted to take Ian and Dylan with her. It would have broken me, although the alternative now is much more crippling.

Police thought I did it on purpose to keep the kids with me.

5 years ago, when Carla and I were madly in love and a full three years before the start of my breakdown, she would greet me every morning with a coffee and a kiss. Only a kiss on the cheek, though; she hated morning breath. She would whisper that she loved me, audible enough for me to hear but quiet enough not to make our pet cat jealous.

Carla was pregnant with Dylan, so sex was off the cards. I had been led to believe that after the morning sickness, bizarre cravings and natural breast enlargement, sex would be very much on the menu, but with me, at least, that never happened.

I should have seen the signs earlier when she would repeatedly add sugar to my coffee even though I am a Type 1 Diabetic. I mean, I am not talking about an elaborate plan to kill me, more just a general error, but a consistent one.

I should have worked it out.

Carla would walk to the bathroom as if modelling the new Prada range at the Paris Fashion Show. I remember the way her dyed blond hair bounced elegantly off her lower back, slightly obscuring the waistband on her new Victoria's Secret red thong. She said that new lingerie made her feel sexy when her ankles were swollen like tree trunks, and the matching bra was a necessity due to her new cup size.

I used to wonder about the practicality of such attire, but it gave me hope that sex would be a reality again soon. Besides, any negative enquiries as to why she would wear it may have taken sex off the table altogether for the foreseeable future.

He has ordered a croissant now. That's unusual; he would have usually left the coffee shop by now. He would meticulously time the last gulp of his Latte with the final glance at the horse racing pages, thank Mrs Beecham and leave.

I hope he finishes up soon. I have a train to catch in an hour. I have to visit a solicitor to find out what my rights are. I am so worried they will take Dylan away from me. It's just not comprehendible. It's not an option. He is my boy, whatever they try to tell me.

Why didn't she take the blame?

As the phrase goes, don't speak ill of the dead. As much as I adored the ground Clara walked on, she was a prize bitch for the final days of our relationship. We never planned to divorce; it was just a trial separation while she decided whether she still wanted to be with me.

I wanted to put a timeline on how long we would separate. Clara told me to stick my timeline where the sun doesn't shine, suddenly and unusually confident in her abuse. She was at one with the English language when she could be bothered to use it to its full potential. Carla also liked swearing a lot. She was a lot braver when we were not speaking in person.

He has sent the croissant back to be warmed up. Pretentious git. What next? Will he demand a free coffee for his inconvenience? He will probably come over to my table in a moment and take my coffee. What's new? He has taken everything else I had.

Dylan was already three years old when she told me. I had a niggling thought for a while, but you just don't ask the question for fear of the answer.

She didn't tell me voluntarily. I overheard Carla and that murderer talking at Joshua's birthday party. I became suspicious when she offered to help him cut his son's birthday cake. Carla never went near a kitchen; she said that the smell of cooking messed with her Chi.

So, I followed them.

It was easy to stay inconspicuous as his place was filled with an undistinguishable amount of 3-year-olds and their pretentious and loathsome parents, smiling insincerely while eyeing each other's gifts to see who had spent the most.

I had left Dylan playing with Gina's daughter. Gina wasn't moving from her spot next to the overflowing ashtray and her bottle of 'apple juice' that she had brought with her from home for anybody.

I situated myself just around the corner from the kitchen door by the unused speaker system that looked like it had its day in the 80s. Looking intently at the speaker and with Carla, knowing how much I love music, gave me a solid and static alibi if they had caught me listening to them.

Some people use the phrase 'being kicked in the gut', but I'd like to invent a new phrase here and now. I was slapped, kicked, punched, and had my balls ripped from me in the space of 30 seconds. I am going to describe this attack as a 'complete organ annihilation'.

When are you going to tell him that Dylan is mine, Clara?

12 words. That's all he needed to say to put me into stunned silence. I missed Carla's response. The world went dark; my hearing was of someone about to faint. My surroundings echoed as the speaker system whirled on its axis from the weight of my back as it hit down hard against the handle.

I picked myself up from the slump and ran into the kitchen.

Their lips were locked; he had one hand on the cake stand so that Thomas the Tank Engine didn't roll from his marzipan rail and the other hand cupping Carla's right butt cheek.

It felt as though they both saw me in unison; his hand only moved a couple of seconds later as he realised where it shouldn't have been.

Their faces levied surprise, fear, regret, and pity. Yes, pity was the primary expression.

My mouth opened, but I had nothing to say.

Of course, he can't cut the croissant properly. The Barista has just cut it for him and even buttered it. He couldn't even open the small butter container for himself. He is getting all the pity now. Somehow people are empathetic to him since everyone found out who Carla really loved. The local paper had seen to that. They called me the psychotic, jealous husband and him the knight in shining armour ready to whisk Carla away from me and save her from my abuse.

Supposedly, I was controlling; 'very coercive' was the phrase the courts told me. I wouldn't let her go out or see friends. She was happy to stay with me, and when she did want to go out, I would remind her that I was all she needed. It's none of their business. Carla didn't want to go out much anyway. Her hobbies weren't worth doing. She knew that I told her enough times.

Everyone blames me. I know it was wrong.

I just wanted him to spend a few nights in jail, teach him a lesson, and give me time to convince Carla to stay. Let me bring Dylan up as his dad. I am all Dylan has ever known. He can't call someone else dad; that would have broken me.

I didn't consider that this fat idiot in front of me was a recovering alcoholic; he hadn't touched a drink in years. I thought I had planned it meticulously; I just hadn't catered for his lack of alcohol tolerance and, of course, Carla lying to me.

Carla had moved out; she was returning to get a few things, which I delayed her from doing until the day after she'd planned to come. I was trying to keep things amicable, make Carla fall in love with the person she met all those years ago, the person who romanticised her for months. I needed him out of the picture for a few days.

I followed him to Mrs Beecham's, sat behind him, and waited. I only needed a couple of seconds to put the gin into his coffee; the sugar would absorb most of the flavour. I served him right for having a high-sugar diet; his tastebuds were wrecked.

After he gulped down his coffee, he left, and I followed him, both of us getting into our cars. I immediately put my Bluetooth on for hands-free phone access and waited for him to start the engine. The plan was that I would follow him for 2 minutes, then phone the police and tell them that I had seen someone drinking excessive amounts of alcohol and was now driving their car, get him arrested, a day or two in the cells. I could make sure Carla understood it was me she needed without his constant presence in her life.

At that moment, my plan backfired. Carla arrived, smiling broadly like a lovesick puppy, and jumped into his front passenger seat, kissing him fully on the lips before he took the handbrake off and started to roll away.

She was supposed to be at her mum's.

They moved away, and I followed, delaying my call to the police, wondering if Carla would become complicit in the crime if they stopped him.

I wish I had called them sooner.

Five minutes later, Carla lay there dying in my arms. He had lost control of the car and ploughed into a tree. The police said that she didn't stand a chance.

He is leaving now. Mrs Beecham, like every day, stood by the slightly wonky, open archway of the door and stared at me. She would make me wait for 5 minutes until he was long gone. Nobody messed with Mrs Beecham. She had long ago stopped staring at me with those piercing eyes. You can't be the nicest woman in the village and hold grudges; she had an open-door policy for everyone—even murderers.

Even murderers like me.

c. Ricky Cibardo 2024

All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced without permission

Write a comment